One of the principles in the first edition of *Extreme Programming Explained* was “40-hour work week.” Wisely, the early XP practitioners recognized that overtime burns out a team and tends to make your product quality worse.

In the second edition of the book, though, the principle had changed to “sustainable pace.” Humans, it turns out, aren’t machines where you just need to keep the overall work cycles down so they don’t wear out. Rather, we have weeks where we work hard to achieve a goal. And then we have weeks where we recover. We’re seasonal (and the demands of product development often are, too).

Taking a broader view, sustainability in product development is about more than just how many hours the team works.

Sustainability includes things like work that’s interesting and engaging for the people doing it, quality that’s stable or improving over time, and a business model that works over the long term.

To evaluate your team or organization’s sustainability ask, “Could we keep working indefinitely the way we’re working now?”

If the answer is something like…

- “No, we’ll burn out”

- “No, we’re taking on more and more technical debt that’s eventually going to have to be paid off”

- “No, people will get bored and leave”

- “No, we’re using up or wasting some non-renewable resource”

- “No, our business model won’t work long-term”

…then something needs to change in your work system.

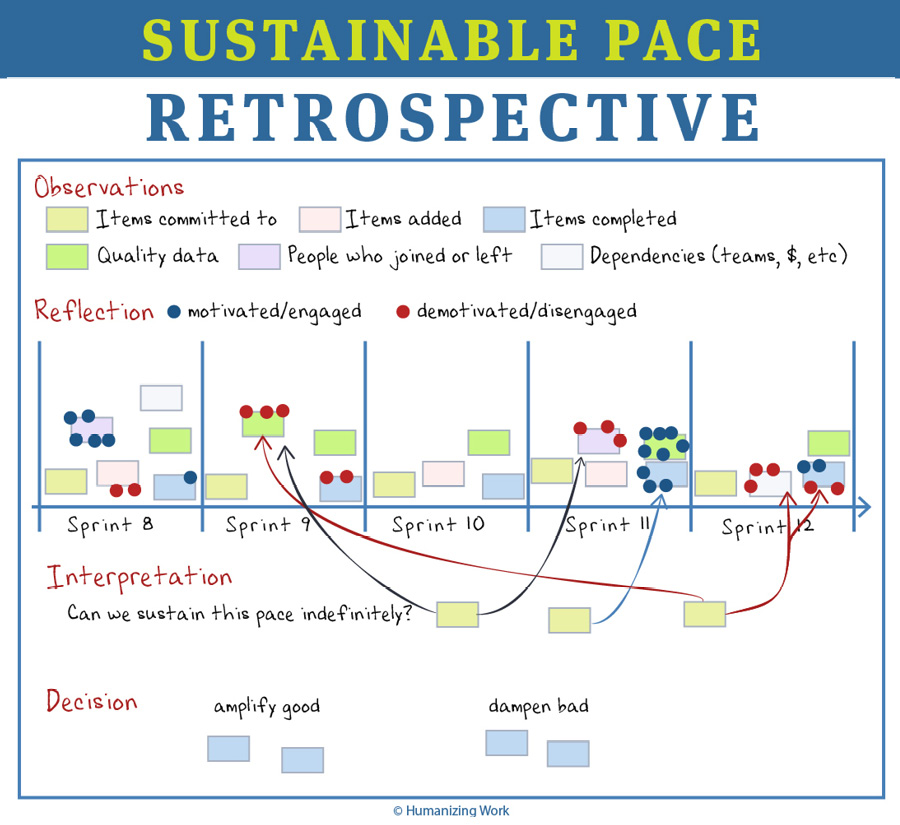

Consider using a retrospective to focus on sustainability. You may discover some important changes that wouldn’t come up if you’re just looking at the last sprint or project. Zoom out and look across several sprints or months. Here’s how…

You can use the ORID approach from The Art of Focused Conversation that we often talk about in our facilitation training.

The O stands for observation. Start by collecting and making visible data that will help you reason about sustainability together. For example…

- How much work did we commit to? How much got added? How much was completed?

- What changed with respect to the quality of our product? Capture any data that would help you see this.

- Who joined and left the team over the period we’re looking at and when?

- What resources (human, financial, material, etc.) did we depend on over this period? Where did they change?

It may be useful to capture this in a table or a timeline.

The R stands for reflection, data about people’s internal state relative to the objective data. We find it useful to visualize motivation levels for this sort of retrospective. This can be something like giving people colored dots to apply to the table or timeline—a few blue for when they were particularly motivated or engaged, a few red for when they were particularly demotivated or disengaged—or it can be a line graph for motivation level over time.

I is for interpretation. Have a conversation to make sense of the objective and reflective data. The key question will be, “Based on what we see here, could we keep working indefinitely the way we’re working now? Why or why not?” This part of the retrospective isn’t just about sharing opinions. You’re making arguments to try to align. Point to the data that supports or refutes an argument. Where people struggle to find alignment, that may be a sign someone has data that’s missing from the board. Add it.

Finally, once the group has aligned around some interpretations, move on to D, decision. Discuss what experiments you can run to amplify the factors that currently contribute to your team’s sustainability and to dampen the factors that make your team’s work unsustainable.

Want to learn more about how to facilitate this kind of powerful retrospective for your team? Join Peter’s Certified ScrumMaster workshop.

Or if you’re a leader, and you want to create an sustainable organization, sign up for our Humanizing Work Leadership Academy intensive series this summer.

Last updated