If the wildcard makes sense, it’s probably not disruptive enough to do the job.

In this episode, we explore what great facilitators do when their teams hit a rut. Through real-world examples—including a pivotal moment at Intel and a breakthrough in a Scrum team’s retrospective—we illustrate how introducing a wildcard can shift perspectives and unlock solutions. We’ll summarize the science behind why these unexpected prompts work. Check out our curated list of wildcard techniques you can use to unlock your team’s problem-solving approach and get them unstuck.

Resources from the Episode

- Wildcards Resource

- 80/20 Product Backlog Refinement Course

- Email us: mailbag@humanizingwork.com

- Connect on LinkedIn

: Checkout some of our favorite wildcard techniques

: Learn more about working in thin vertical slices

: What’s a question, prompt, or constraint you’ve used to shake things up when your team was stuck?

Episode Transcript

Peter Green: Every great team that I’ve been on, or worked with, or read about, they all get stuck sometimes, trying to solve really hard problems. Now, sometimes we can talk our way through to a solution pretty quickly, but other times, for whatever reason, it feels like we’re never gonna figure it out.

We might even consider giving up, assuming the problem’s just not solvable for us. We’ll just have to deal with it. Maybe we even start figuring how to spin it a little bit so we don’t feel so bad. We’ll say things like, “we may need to explore a pivot here…”

Richard Lawrence: And there probably are times where pivoting is the right course of action, like if you’ve disproved a core assumption. But if you’re giving up on solving a hard problem, just because you’re out of energy or new ideas, you might appropriately wonder, “what if we had just given it one more try? Would that have been the time where we figured it out?”

Peter: Richard, when a new driver gets stuck in the snow, their first instinct is to…

Richard: Hit the gas.

Peter: Hit the gas, right? Which just digs them deeper in, and all of us who facilitate meetings know what it feels like to be spinning your wheels in a meeting, with the mounting pressure to get to a good answer. When that anxiety ramps up and the team’s looking to you to figure out what to do next, it’s tempting to keep pushing, trying harder, going deeper.

But that’s the wrong move if you need creative solutions to intractable problems. If you’re facilitating, you need to ask different questions, to take the team on a left turn, or get outta the proverbial car altogether and put a piece of wood under the tire. Maybe we’ve stretched that metaphor as far as it’ll go, but facilitators need to be in the business of jiggling the team’s thinking in a different direction.

Richard: Now, Peter, when you use the word intractable, the root there is traction, well played.

Peter: That was not an error.

Richard: So in today’s episode. We’re going to share how to use what creativity researchers call ‘wild cards.’ We’ll give you a few real examples, share why they work, and point you to a resource we’ve created with our favorite wild card techniques in seven different categories.

But before we do, a quick reminder that this episode is brought to you by the Humanizing Work Company, where we help organizations improve their leadership, product management, and collaboration. Visit humanizingwork.com to learn more about our workshops, coaching and online courses, or to bring us in to support your team.

Peter: And if you get value from the show and you wanna support it, the best thing you can do if you’re watching on YouTube is subscribe, like the episode, and click the bell icon to get notified of new episodes. If you’re listening on the podcast, a five star review makes a huge difference in whether other people who’d benefit from the show find it or not.

Richard: The first example of a wild card that came to mind when we were talking about this topic is a famous conversation between Intel co-founders, Andy Grove and Gordon Moore. At the time, Intel’s primary product was memory chips, but they were thinking about getting into processors. They couldn’t afford to invest in both. Memory chips had been their cash cow, but lots of low-cost competitors had entered the market. They hadn’t proven that new market or their technology and processors though, so it would be a risky shift.

After weeks in back and forth, Grove finally threw in a wild card. He asked, “if we got kicked out, and the board brought in a new CEO, what would he do?” Moore responded without hesitation, “he would get us out of memories.”

Grove then suggested “then, why shouldn’t you and I walk out the door, come back in and do it ourselves?” This led to Intel’s strategic decision to exit the memory business and focus on microprocessors, a move that transformed the company into a dominant force in the tech industry.

Peter: I love that example. Thinking about the problem from someone else’s perspective got them unstuck. It immediately became clear what they should do. I kind of like the ceremonial aspect of it too. Like let’s walk out the door and come back in as a new leadership team.

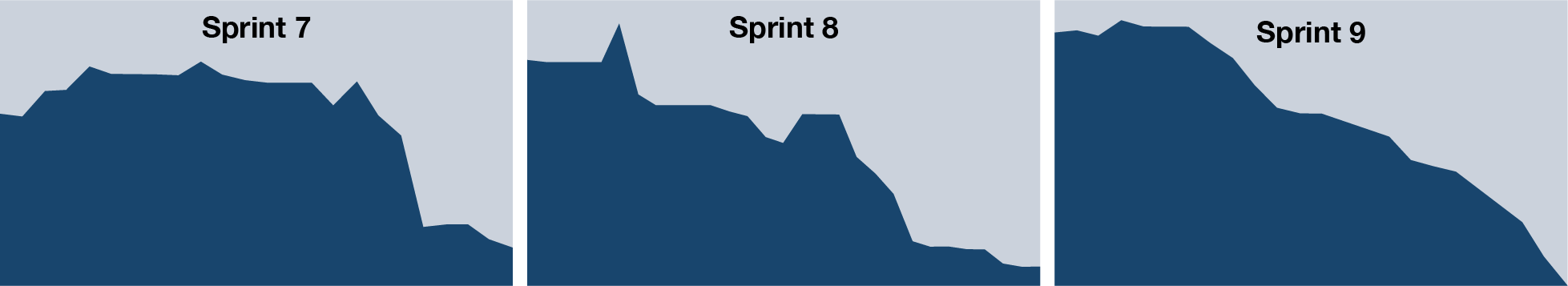

That situation reminds me of Sprint eight for Adobe Audition. When our team adopted Scrum eight sprints earlier, we set a goal to get everything releasable by the end of a sprint. But month after month, we failed to do that. Almost always, we’d run out of time for testing at the end of each sprint, and move those testing tasks into the next sprint. The same pattern would repeat itself.

Every retrospective, we tried something different: earlier handoff deadlines in the sprint, different processes for submitting code, builds, testing, documentation, bringing QA in earlier—and nothing worked. We were just spinning our wheels. At the end of Sprint eight, I was at the end of my rope as far as ideas for how to fix it.

I had put a lot of political capital on the line advocating for Scrum, feeling intuitively like it should work, but not knowing why we couldn’t break through on this problem.

Around that time, I attended a coaching class where the trainer taught us a technique to help people in conflict get unstuck. The coach used a deck of cards, each with a random image. In class, we invited people to pull a card and use it as a metaphor for the relationship. It often uncovered something they hadn’t talked about yet—and it usually worked.

Later, while planning the Sprint 9 retro, I noticed the cards on my desk. And it hit me: these aren’t just for conflict resolution.

So I opened the retro by sharing our usual pattern—yet again incomplete testing, same burndown chart shape. Then I spread out the cards face up and asked each person to pick one they liked. Then I said: “Tell a story about how your card is an illustration in the article we’ll write about how we finally got testing done in Sprint 9.”

Some people rolled their eyes, but they played along. One QA person picked a card with a scientist in a lab and said: “In the article, the team decided to think like scientists. For every task, they asked, ‘How might we test the result of this?’ It shortened the round trip between code and validation. They finished testing in Sprint 9 hours before the review.”

We tried that in Sprint 9. And it worked. That was our path into small vertical slices. We got almost every task done. The burndown dropped cleanly to zero. I’ll include the charts in the YouTube version so you can see the difference.

Richard: I love doing this kind of thing in retrospectives. It helps teams generate ideas instead of just pulling from a suggestion box. A wildcard like a random image makes the whole thing more collaborative and generative.

And for those listening—when it comes to vertical slices, you don’t have to discover it the hard way like Peter did. We’ve gathered the best techniques in our 80/20 Product Backlog Refinement course. If your team wants to get better at slicing and story writing, it’s worth checking out. Link’s in the show notes.

Okay, back to wildcards. Why do they work?

Psychologists call it lateral thinking or remote association. When we’re stuck, we’re running the same mental loops, using the same assumptions and arguments. Great for efficiency—terrible for breakthroughs.

Tossing in something unexpected—a constraint, a weird image, a flipped question—breaks the loop. And once it’s broken, our brains can’t help but try to make sense of the new thing. That’s where insight lives.

Peter: And that’s why the wildcard doesn’t need to make sense. If it does, it’s probably not disruptive enough. It needs to be a left turn. Something jarring enough to shift how we’re thinking.

Richard: That’s also why we have people pick an image before they know what they’re going to do with it. If you choose an image to match your idea, it’s not a wildcard. The randomness matters.

There are way more wildcard techniques than we could share in one episode. So we made a resource: humanizingwork.com/wildcards. It includes different types of wildcards, why they work, and links to the Visual Explorer cards Peter used.

Peter: We’re also sharing our Top 10 wildcard questions in the comments. And we want yours! What’s a question, prompt, or constraint you’ve used to shake things up when your team got stuck? Drop it in the comments—we’d love to learn from you.

Richard: Thanks for tuning in to this episode of the Humanizing Work Show. We’ll see you next time.

Last updated